Canada: the second largest country in the world, with one of the lowest population densities. The very name brings to mind vast, rolling expanses of natural wilderness, untouched and unspoiled by human activity over millennia. Unfortunately, for Canada’s aboriginal First Nations population, who make up the vast majority of those who call the most rural and isolated parts of the country their home, this supposedly pristine lifestyle can be anything but. And one of the crucial issues affecting First Nations communities is the availability of safe, clean drinking water.

A Global Problem

A staggering number of people around the world do not have access to water sources that are free from contamination – 1.1 billion according to the World Health Organization. This lack of clean water brings with it many problems. Worldwide, more than 840,000 people annually die from water-related diseases, mainly caused by contamination from various pathogens, as well as from toxic chemicals. Such issues are often thought to be confined to developing countries, where despite these statistics great strides have nevertheless been made in improving water safety and security.

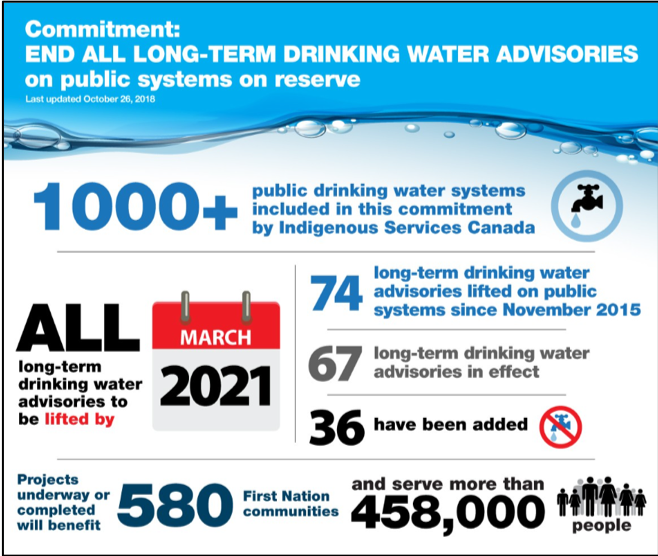

However, these problems also plague Canada’s First Nations communities. Health Canada still estimates that between 110 and 130 communities need to boil their water, and 85 communities are at risk of their water systems simply breaking down. In all, around 20,000 aboriginal people living on reserves across Canada do not have access to running water or sewerage.

The Right to Water

There is often a strained relationship between the government of Canada and the First Nations population, and this is particularly pronounced in terms of water rights. The Canadian government has consistently refused to accept that aboriginal people have a right to water. Despite this, there have been many First Nations legal challenges to the federal and many provincial governments as to their responsibilities to provide water to isolated areas. Adding to the frustration of many communities, there have been no court cases in Canada that have ruled one way or the other.

There are problems with access to water in other remote communities in Canada – for example, the E. Coli outbreak in Walkerton, ON in 2000 that killed 7 people – but things are even worse in First Nations. Similar problems abound in aboriginal communities in Australia, where a considerable health disparity exists between aboriginal and non-aboriginal Australians due in part to the lack of clean water on isolated reserves. For both Australia and Canada, the treatment of their aboriginal peoples in terms of water rights is a key social justice issue.

Bottled water has been used as a stop-gap solution, and Ottawa has spent at least $2 million flying in bottled water to Marten Falls First Nation, which has been under a boil water advisory since 2005. Unfortunately, the result is not only that money that could have been used to repair the reserve’s ailing water treatment facility has gone on transport and bottling costs, but the reserve’s landfill is now full of plastic bottles. In response to issues like these, and to highlight the necessity of safe drinking water in First Nations communities, some reserves have banned the use of bottled water entirely, like Tsal’alh in BC. And of course, in BC, there are issues with large companies such as Nestlé bottling water ‘too cheaply’ despite the province struggling with drought.

The Unfiltered Truth

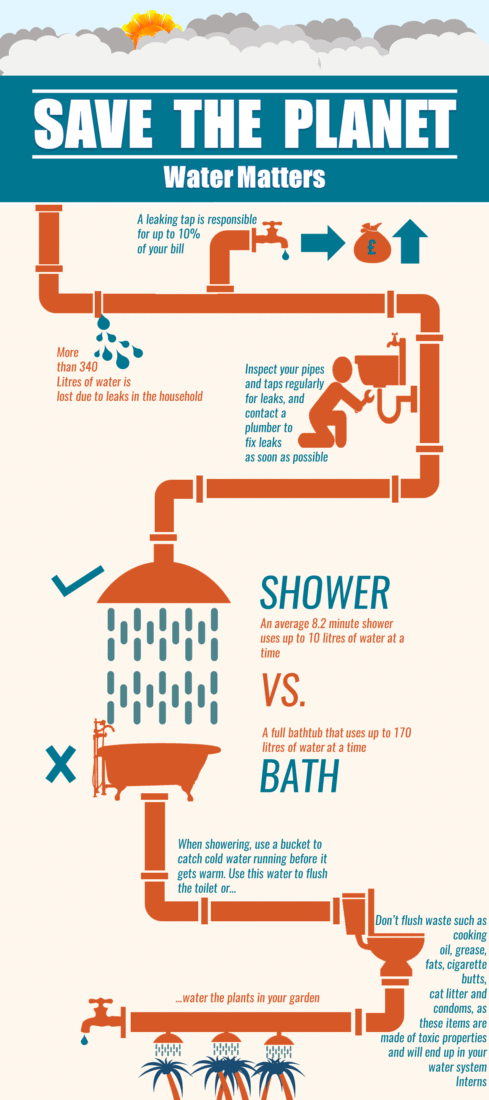

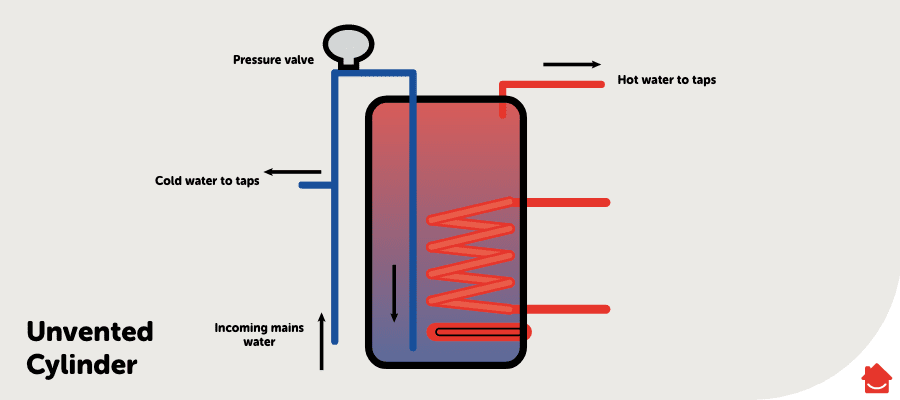

So what’s the best way forward? Well, in developing countries, the use of ceramic water filters can reduce the amount of infections by pathogens dramatically. Membrane and reverse osmosis filters are even more effective at reducing various contaminants. Reverse osmosis filters work by applying pressure to a solution with a high concentration of contaminants to force water molecules through a membrane into a solution with a low contaminant concentration. The limiting factor has always been the membranes used in the filtering process, but technological advances in membrane manufacture have allowed the process to become much more efficient. Crucially, reverse osmosis systems are fairly inexpensive because of the decreasing cost of these membranes.

Most Canadian municipalities and provinces have sophisticated water filtration plants that can provide clean tap water and halt contamination from wastewater on an industrial scale. Advanced and environmentally sustainable water treatment is urgently needed to allow isolated First Nations communities access to safe drinking water, but the limiting factor has always been cost. Recently however, with the scandal around residential schools and the Idle No More movement, which seeks to improve First Nations access to the land and water, Canadians are waking up to the injustices that aboriginal peoples face. With a change in the federal government looking likely this Fall, will Canada finally be able to face up to the challenges of providing clean water for its aboriginal citizens?